The new documents are somewhat challenging to find on the less than user friendly PTD website. A lot of effort has gone into improving the site, and it has improved, but it is still a disjointed jumble. The PTD site is separate from the QCD, which is separate from QTenders, which is separate from the conditions and guidance site, which of course is all separate from the GITC site. The new documents are in fact buried in the Buyer side of the procurement site and I have not seen any reference to them from the Seller side, which is a shame because it is just as important that the suppliers understand the framework as the procurement advisers. To save you the challenge of tracking them down, you can find them here.

In this blog I’m not going to go into great detail around the technicalities of the contract frameworks (other than pointing out a few items that stand out), instead I will focus on what I have worked out about how they function and how to use them to engage the market and bind a contract. Some of what I have reviewed in this blog has changed in the life-cycle of writing the blog, and I suspect as more Departments review and start using the documents the changes will increase, so make sure you use this information as a guide only and take the time to carry out your own review.

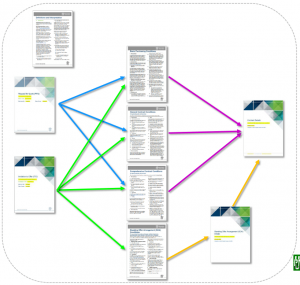

Changes in the Structure

The new structure is made up of two major parts, the invitation documents and the contractual frameworks. In my opinion, maintaining the separation of these components is a great move, the invitation documents aren’t tied to any contract, so you can mix and match the components to build a procurement process and contract framework that suits the characteristics of the requirement. Simple process, simple contract, simple process strong contract, complex process simple contract, and so on. The invitation documents are even designed to allow the use of non-standard contracts where you have a very specific and unique requirement. This approach provides a great deal of flexibility for the buyers to tailor their process and contracts as required while maintaining a level of consistency in what the documents look like and where to find information.

In implementing this structure, they also broke the Definitions and Interpretations document out into a separate standalone document. This fixes the irritating inconsistency of terminology and definitions between contract frameworks in the previous model. One definition applies to all invitation and contract documents, fantastic.

Speaking of Terminology

My most favourite change in the terminology used is the shift from calling the contracted party the “Contractor” (and yes I do recognise I sound like a real nerd when I have a favourite change to a contract framework). Defining them as such caused challenges in ambiguity where a Contractor in the contract was supplying a contractor. Under Queensland State Procurement Policies, contractors are resources who provide professional and non-professional services and there is guidance to differentiate between a contractor and a consultant, so having a Contractor also being the defined term for the service provider was a nightmare (GITC users, your pain continues). The new term is now “Supplier”. The term “Offeror” has also disappeared from the invitation documents and is also supplanted by the new term “Supplier”. I can’t say that I am overly thrilled by the use of the same term for an entity making an offer and an entity under contract, that could also cause some confusing conversations, but we will see how that goes, at least spell checker won’t keep complaining about the legal terminology of “Offeror”.

The New Contracts

There are now four contract frameworks to choose from:

- Basic Purchasing Conditions

- General Contract Conditions

- Comprehensive Contract Conditions

- Standing Offer Arrangement Conditions

As you can guess from the titles, these offer a sliding scale of complexity in contractual terms. To help select the contract framework to use, there is a Decision Tree – Contract Selection document at the bottom of the page. This guidance is very high level and unfortunately leaves you with more questions than answers. Far more useful are the individual “When to use…” documents you will find with each conditions document. These are infinitely more helpful documents and after giving the decision tree a quick glance, I wouldn’t bother opening it again.

The “When to use..” guides are simple one-page documents that provide some high level guidance on thing’s to consider when choosing your contractual framework. This is great for less experienced procurement officers and first time users of the frameworks as it gives a quick overview of the intent of each contractual framework, but they don’t absolve the end user from ensuring they understand the contracts and the risks associated with using each of them for their specific requirement.

A general comment on the new frameworks is that they are far more “readable” than the old frameworks that were rife with legalese jargon. Now someone with no legal training can get an understanding of what the intent of a clause is. For an example of the simplification and improved readability of clauses, compare the clause for the Term of the Contract:

Old Conditions of Contract

3 CONTRACT TERM

3.1 The Contract Term will commence on the Commencement Date and, unless terminated sooner in accordance with clause 31, will continue until the earlier of the:

(a) date when all Deliverables have been provided by the Contractor to the Customer and the Customer has given Notice to the Contractor that the Deliverables have been supplied and completed in accordance with the Contract; or

(b) Completion Date.

3.2 If the Deliverables have not been supplied and/or performed by the Completion Date, the Contractor must seek an extension of the Completion Date from the Customer, in accordance with clause 28.

New General Contract Conditions

3 TERM

The Contract starts on the start date in the Details and continues for the period set out in the Details, including any extension options which are exercised.The Customer must give notice of its intention to exercise any extension option.

This move to a more comprehensible and less verbose language should significantly reduce the number of ambiguous and poorly constructed contracts, and reduce the risk of unfamiliar suppliers agreeing to terms they should not.

Basic Purchasing Conditions

- It is clearer about withholding payments for disputed value

- Intellectual Property is set as Supplier Owned with a license for use by the Customer

- Liability is fixed at 1.5 time the value of the contract

- There is no treatment for Key Personnel, so this framework should never be used for engaging contractors or services other than getting a plumber to clear the sink.

- This basic contract also lacks the “No Advertisement” clauses of the old model.

The last one I suspect must have been an oversight. This is a clause that is very inconsistently applied by Government, but it is important. The clause precludes Suppliers from advertising the work they are doing with Government. If you visit the websites of many organisations that work with State Government, you will see Departments listed as customers, news stories about getting new contracts and even case studies. All of these are in breach of the “no advertisement” clause. Why is this important, well there are a number of thing’s:

- Government should not be seen as endorsing any product or service.

- Allowing a Government Department to be listed as a customer could be perceived as favouritism

- The listing also provides a potential leakage point for information about how a project or department functions

Leaving this clause out is an inconsistency, because it exists in one form or another in the General and Comprehensive contractual frameworks. It is a potential loop hole for any suppliers that manage to get awarded a basic contract that permits them to list a Government Department as a customer. The general advice I would give is that even though this contract is a little better than the old Short Form Contract, I would still steer clear of the Basic Contract for anything other than low risk, off the shelf goods and services.

General Contract Conditions

In the blurb about the new framework, the General Contract Conditions are intended to replace the woeful Short-form Contract from the old framework. This made me immediately nervous as the old short-form was not much good for buying anything other than the forks in the kitchen drawer, and even then I would be worried. The General Contract Conditions sit in the mid range of complexity and as such is likely to form the bulk of contracts awarded in volume if not value. It is pleasing to see that the contract is only nine pages long as opposed to the 21 pages of the old Conditions of Contract, though to be fair, the old contract included a cover page, interpretations and definitions. in comparison to the Basic Purchasing Conditions, the General Contract Conditions provides more extensive treatment of liability, Indemnity and Intellectual Property. Generally, it is an effective and usable contract. There are some gaps, but the Contract Details document provides additional provisions functionality to allow these gaps to be closed.

The new contracts no longer have the two IP options of the old model, instead existing Intellectual property rights are retained by the original owners of that property, but all new IP generated in the course of the contract is owned by the Customer and the Customer grants the supplier a license to use the IP as they wish. This is a reversal of the old clause 18.4 of the Conditions of Contract. In practice it ensures the Government owns the IP it has paid for while allowing Suppliers to benefit from the work as well. Special consideration will need to be given where the IP is tied up in a confidential report that you don’t what shared or where there is potential for the Government to want to commercialise the resultant solution and a private sector competitor with the same IP would be undesirable. Alternatives for the IP clauses are available in the Clause Bank document discussed later.

Out of interest, an early version of the contract conditions had the IP owned jointly, but this model is problematic where one party can demonstrate they did most of the work to develop the IP, in those cases the courts will often award sole ownership to the party that did all the work. Where Government engagements are concerned, suppliers are generally engaged because the necessary knowledge and skills required to develop the IP are not available, so joint ownership is not a good option.

The other reversal to watch out for is that under the old model, all confidential information provided to the Supplier had to be destroyed or returned at the end of the contract unless written permission was obtained from the Customer. This is why the larger consultancies ask for a caveat on “working copies”, so they could retain the information for their own purposes. Under the new contracts, the Customer has to remember to ask the Supplier to destroy or return the confidential information. Given the poor record of even enforcing the original clause, the outcome is going to be pretty much the same, however, the change is concerning as it is unlikely many projects will remember to take this step and so now the onus of protecting that data has fallen on the Customer rather than the Supplier.

Comprehensive Contract Conditions

The new contract framework is a layered approach with each new level retaining the clauses from the lower level and adding new component, so the comments above are equally applicable to the Comprehensive Contract Conditions. The Comprehensive Contract Conditions extends the length of the contract out to 10 pages and expands the clauses that cover Securities in more detail. It also expands upon rights to set off amounts payable to allow the customer to access Securities. In the General Conditions, Securities is mentioned in one clause in the Supplier General Obligations section, in the Comprehensive Conditions it gets a section of it own and is treated in detail. So if you require a security for you’re contract, consider the Comprehensive Conditions.

Also in the Comprehensive Conditions is consideration of Transition Out requirements for the contract (something that is sadly overlooked in many high value, high risk contracts. The treatment is very broad, as it must be in an approach that uses templates, so you still need to give careful consideration as to what you expect from the Supplier during transition out and document the agreed position in the Contract Details.

Standing Offer Arrangements (SOA)

As we all know, an SOA is not a contract and as such it needs to have a model for forming a contract under the SOA. The new framework has approached this requirement in an interesting way by allowing the end user to leverage the three available contract frameworks of Basic, General and Comprehensive, to define the Customer Contracts. This is achieved through identifying the applicable contract conditions in section 3.3 of the SOA Details document. I like this concept, but I’m not convinced the application is complete and clear. For example, the SOA Contract Conditions duplicates some clauses that are in the contracts. Despite this, there is nothing to document the hierarchy of the various documents in forming a contract under the SOA. This could lead to some confusion in determining the applicable clauses where there are duplications.

One clear instance of this is in the IP clauses. The SOA takes the same position as the General and Comprehensive Contract Conditions, so there is little to be concerned about if you are using one of those frameworks, but you can use the Basic Contract Conditions as your contract framework for the SOA. In this case the IP Rights are all assigned to the Supplier, the exact opposite position. Without a clear hierarchy, this could raise some questions as to which applies. To further complicate the matter, all the contract frameworks include a clause along the lines of “Unless otherwise specified in the Details, all the terms and conditions of this Contract (including this clause) will survive termination or expiry of the SOA, for any reason”. So when the SOA expires or terminates, you could find yourself with a very different outcome for your IP ownership where the Basic Contract has been leveraged.

The old SOA framework needed to have the conditions of contract embedded as it was a standalone solution, given that the new approach is aimed at leveraging the other three contract frameworks, it is a little odd that any contractual conditions are included in the SOA document at all, and a review would be good to remove all but the SOA specific clauses from the SOA level.

Moving on from that, once you have defined the applicable contract framework in Section 3.3 you then go on to Schedule 5 to define how an order is to be placed under the SOA. There are a couple of things to watch out for here as well:

- The definition of an SOA Order is “SOA Order means any order or acknowledgment from the Customer for the provision of Goods and/or Services that are the subject of a SOA.”, this fails to make any reference to the Schedule 5 of the SOA and really allows users to issue what ever they want to form a contract. So you need to make sure potential users know how they should form a contract to ensure the terms negotiated with suppliers are enforceable by both sides

- Schedule 5 makes absolutely no reference to the contractual framework identified in Section 3.3

- The example template provided makes no reference to the SOA

With all these things in mind, I would recommend re-writing the whole of Schedule 5 to make sure it describes exactly how you have agreed with the Supplier that contracts will be formed and and derogate the definition of an SOA Order to reference Schedule 5. Depending on the complexity of what is to be purchased under the SOA, I would give consideration to leveraging the Contract Details model for end users to form the contracts, reserving the basic example provided for purchasing off the shelf products with fixed specifications (don’t forget to add a field referencing the SOA as well). It would also be a good idea to embed the hierarchy of documents into the order form to alleviate any confusion.

The concept being applied is once again great for allowing the procurement advisor to mix and match the available frameworks to define an SOA that suits their requirement, but make sure you take the time to provide the suppliers and users with a clear understanding of what clauses apply, the hierarchy and how exactly a contract is to be formed.

How to form a contract

1.3 Hierarchy

If there is any inconsistency between the documents which make up the Contract, then the following will prevail in descending order of precedence :

(a) the contract departures section of the Details;

(b) the Schedules to the Details (excluding any document incorporated by reference);

(c) the General Contract Conditions

(d) the Details (excluding the contract departures section of the Details);

(e) any document incorporated by reference.

Note that there is no mention of the Letter of Acceptance in this hierarchy, so where does it fit in where there is a conflict?

Note also that there is no reference to the RFQ/ITO specifications or the offer, that is because the Contract Details document is embedded in the invitation, in fact in the RFQ document, there is no option for defining requirement or requesting responses to criteria, but more on that later.

Note further the capitalised “D” in “Details”, this is a defined term that unfortunately demonstrates some inconsistency in the framework in its early release form. This I will covered in discussing SOA formation, but suffice it to say that if the contract is not under an SOA, Details means Contract Details, which is embedded in the RFQ and ITO documents when you release them.

There is some intentional vagueness in forming a Basic Purchasing contract. I say intentional because I suspect it is geared so that a Basic Contract is formed by issuing a Purchase Order. I say vague because the conditions refer to the contract forming when the Supplier accepts a “Basic Order” and the definition of a Basic Order is “any form of order from the Customer for the provision of Goods and/or Services which incorporates or refers to the Basic Purchasing Conditions”. So if your PO template includes a reference to the basic Purchasing Conditions as a minimum, then you are good to go. Keep in mind though that the Supplier must be made aware that you intend to enforce a Basic Purchasing contract when you request the quote. If their quote includes their terms and conditions and you simply issue a PO, then there may be an argument about which conditions apply, particularly if the PO reference is unclear or incorrect. You would most likely rely on the order of events to determine the outcome, but that is likely to result in a longer, more expensive court battle and could well be undermined by behaviours between the parties post PO issue.

Letters of Acceptance and why I avoid them

The other big issue with Letters of Acceptance is that if anything has been altered through clarification, addendum or negotiation, you need to spell it out in the Letter of Acceptance, in which case, you might as well assemble a Contracts Details document, in fact, in the signature block for the Contract details template is the following statement:

If the parties agree any changes to this document after the date of the Supplier’s signature (but before the Customer accepts the Supplier’s offer as described below), the Supplier and Customer will prepare a new version of the document incorporating the agreed changes, which will replace this document. The Supplier will sign the new document, offering to enter the Contract on the amended terms.

This indicates that a Letter of Acceptance including changes to the contract is discouraged and instead, the Contract Details should be updated and reissued to the Supplier.

The signature block for the Customer states:

The Customer may accept the Supplier’s offer either by signing in this section, or separately confirming to the Supplier in writing that the Customer accepts the Supplier’s offer.

This opens up the opportunity to use a Letter of Acceptance, but it is really getting silly by this stage. Do yourself and your successors a favour and put proper countersigned contracts in place. Remember also that a Letter of Acceptance must either be signed by, or if in email form issued by, a delegate authorised to bind the State, so Letters of Acceptance really are pointless.

Contract and SOA Details

There are only two Details documents available under the framework, one for forming an SOA, the other forming a contract. The Details documents are the tool for tying the contract or SOA together. In both cases, this is where you define the conditions that apply (Basic, General or Comprehensive), identify the parties and accurately describe what is to be delivered and when. The documents replace the Schedule 1 for the SOA and the Schedule A for contracts and combines all the other schedules for pricing into a single document. Section 2 General Information for both documents is highly reminiscent of the old Schedule A, providing a tabular format for capturing the key information regarding the contract. Once you are past that, the rest of the document is a freer form of paragraphs documenting other aspects of the agreement.

The invitation documents have been designed to include the Contract Details as the primary offer response document. This has given rise to the oddity that the contract departures are split into Customer generated departures and Supplier generated departures. The guidance note in the Suppliers Changes section indicates that the Suppliers departures supersede the Customers departures, however this is not recognised in the General or Comprehensive Contract Conditions, they both merely reference “the contract departures section of the Details”. I suspect you would be relying on the order of events to determine the applicable clause. The Customer defines departures, the Supplier adds modifiers to the departures, letter of acceptance is issued and so the last changes made before acceptance have precedence. But what if the Supplier was the first to put in departures with their offer and the Customer modifies it with their section, how could you see that activity 6 months down the track when you inherit the contract? This configuration is also trap for anyone planning on simply issuing a letter of acceptance as there is a likelihood that if they reject the requested departures, they could be making a counter offer for the Supplier to reject.

When using these templates, as a final stage of the process leading to forming the contract, I would consolidate the two sections into an agreed position and issuing the final draft contract to the Supplier for them to sign.

I really think the inclusion of signing in counterparts removes any need for letters of acceptance and I’ll discuss this in the General Comments and Considerations section below. Outside of that oddity, the rest of the document (in both examples) flows in a logical and easy to understand format. I think they will actually help users to build better quality and more complete contracts.

Invitation Documents

- Invitation to Offer (ITO)

- Request for Quote (RFQ)

As mentioned earlier, the invitation documents are configured to allow the end user to select any of the four contractual frameworks available, with the exception that an ITO is assumed if the intent is to establish a Standing Offer Arrangement (SOA).

The conditions of offer are now embedded in the to invitation templates, this is handy for suppliers who probably never downloaded and/or reviewed the old conditions of offer. The two sets of conditions are identical between the templates other than Clause 1 and 2.1, in the ITO document where these clauses make reference to a potential SOA being the objective of the procurement.

One really concerning omission in the Conditions of Offer, from the Customers perspective, is the ability to accept one Offer, or more than one Offer, for the whole of its requirements; accept separate Offers for any portion of its requirements; accept one Offer, or more than one Offer, for any portion of its requirements. These are pretty important points to provide flexibility in awarding contracts with multiple component portions. These clauses aren’t even in the ITO conditions of offer document that would be used for more complex processes.

The RFQ model is designed so that you issue the RFQ template along with a partially completed Contract Details template and the vendor responds with a fully completed Contract Details template. This model is fine for speeding up the process of generating a contract, but it discourages negotiation and will add complexity to evaluation and documenting the decision making process for selecting a preferred offer. The RFQ document does not provide the ability for the Customer to define evaluation criteria in a way that the offeror has to respond to the criteria, it simply lists them in a cell in the table. If your evaluation criteria is price and delivery date, then that is fine. But if it is more complex than that, the vendors should be given the ability to control, to some extent, how their offer will be evaluated. This is best served by breaking each criteria out into a specific requirement that the Offeror can respond to directly. Listing evaluation criteria and asking the offerors to respond in a general submission invites subjective evaluation that is difficult to audit and defend.

In the case of the ITO template, there is a response document that is pre-populated with open ended headings and guidance.

Loose criteria and vague supplier responses result in one of two evaluation paths, highly biased or price based. In any case, it removes some of the control the vendor has over how their offer is evaluated and increases the level of subjectivity the evaluation panel applies to evaluating. It is also important to recognise that though invitation templates have been provided, there is no guidance at all for how to evaluate with these documents other than the broad Guidance notes available on the Procurement Guidelines site. The final design of your invitation documents is very much driven by the approach you will use to evaluate the offers, so you should build your evaluation tools at the same time as you build your invitation document. For low to medium risk/complexity procurements, I advise my clients to develop an invitation/evaluation suite that allows the rapid development of documentation and a consistent approach to evaluation. Not only do the templates lack this guidance, in their current format, they potentially drive poor procurement practice by relying on the evaluators interpretation of the offerors intent rather than allowing the offeror to determine how their offer will be evaluated.

The ITO document also includes a Schedule encouraging “innovative” offers. While I am all for innovation, the worst nightmare of a public sector procurement advisor is an “innovative” offer. The problem, as discussed above around evaluation, is how do you compare an offer that is outside the box with offers that are compliant with the requirements that have been specified. This can be extremely challenging, as is any situation of comparing apples and oranges. You need to design your evaluation process from the outset to be flexible enough to allow non-conforming offers to be evaluated. If you make the criteria too tight, you can’t evaluate non-conforming offers, if you make them too loose the evaluation becomes subjective and open to challenge. The other argument is around what “innovative” means. Submitting a slightly different scope is not innovative, and if an offer is selected based on a different scope to the one published, then there is further cause for challenge by the unsuccessful offerors. If a section like this is to be included, then there should be some guidance on how to manage it. Hint, the answer is outcome focused specifications and criteria, but these are more complex to write and still difficult to evaluate in an objective manner.

General Comments and Considerations

Given that a large percentage of these contracts will be used to engage contractors and services relying on Key Personnel, it is disappointing to see the ability to request a Key Person be changed without question has been removed (though I am sure suppliers will welcome this). There are reasons of convenience for this clause to be there, such as personality conflicts and poor performance, contractors should be easy to swap out that’s why you are buying a contractor. But a more important aspect is that Government may become aware of a criminal record, inappropriate association or conflict of interest of a contracted individual. This path was an easy method of removing the individual without having to divulge personal information of the individual or go through an extended period of review and justification.

A further point to note is that termination for convenience requires 30 days notice, this used to be tempered with “or such other reasonable period as determined by the Customer”, but that has now been removed. Thirty days is excessive for a contracted resource engaged for a project environment, where the project could be terminated at any time or Machinery of Government could make an engagement superfluous.

All of the contractual frameworks refer to receipt of a “correctly rendered invoice”, unfortunately there is no definition of what a correctly rendered invoice is. This is a benefit to Suppliers in some ways, the standard definition in the old framework required references to the purchase order or contract number, the Project Manager, what has been delivered and various other items that really should be on every invoice, but sadly few vendors actually issue a correctly rendered invoice. Even the big four companies who make their bread an butter out of auditing other companies financial processes appear to find it difficult to produce an invoice that defines the PO, Contract and deliverables they are charging for. State Government in most cases could easily reject invoices received as non-compliant. The problem with this bad behaviour from Suppliers though is that it is often quite difficult for the Accounts Payable teams to identify the PO and cost centre owner for invoices received resulting delayed processing and increased workloads.

Expenses under the General and Comprehensive Contract Conditions state that travel and accommodation expenses will not be reimbursed unless the customer requests that the Supplier travel away from the agreed service location. That is a narrow view given that there are occasions when you will need to buy in expertise from outside the local area and you may need to pay for travel to the agreed service location. You would need to remember to address this in the additional provisions for the contract in those cases.

All of these issues can be considered and addressed through the use of section 3.3 of the Contract Conditions, but be aware of your requirements and make sure they are addressed.

On a positive note…

The signature blocks of all documents have now moved away from the requirement to sign under s127 of the Corporations Act, this will save a lot of headaches where the supplier is national or international and access to two company directors is difficult. It also alleviates the need for multiple signature blocks to allow for partnerships and sole traders. The onus is now on the Supplier to verify, on request, that the signatory has the authority to bind the Supplier to a contract.

An excellent change in the contractual frameworks is the allowance for contracts to be signed in counterparts. What this means is that you can receive a scanned copy of the contract from the supplier with their signature and sign that document to bind the contract rather than using the slower and more costly process of having documents moved around by courier or mail. I’ve been using the additional provisions in the old framework to include this functionality since the changes to the Evidence Act abolishing the need for original documents. Now the ability is embedded in the framework through the statement that “This Contract may consist of a number of counterparts and if so, the counterparts taken together constitute one document“. This isn’t my favourite counterparts statement, I prefer the position that each counterpart is an original (as it is in evidence anyway) and together they are one agreement, but again, it is a step in the right direction. The inclusion of this now makes the letter of acceptance approach largely defunct as you can now turn around a Contract Details document as quickly as getting a Delegate to sign a letter of acceptance.

There are some risks associated with the signing of contracts in counterpart, you must be able to demonstrate that the contracts were identical and that the signature is real. The easiest way to support these needs is to save the email the signed contract was send in, print that copy of the contract and have it signed, then email a copy of the signed contract back to the vendor, saving that email as well. The worst outcome is if the last signatory hand writes a change to the contract, then you have to go back to square one and start again.

An interesting thing to note is the new clause 19.3 Criminal Organisation, which calls out the new 60A(3) clause of the Criminal Code, the centre of the so called “bikie laws”. Clause 19.3 requires the Supplier to warrant that neither it nor its Personnel have been convicted of an offense under the Criminal Code.

Also interesting is the comment in the guidance for the documents is that they can be used for low risk ICT Services. I have little doubt that this will be welcomed by the casual GITC framework users who are confused by multilevel and the modular approach of the contracts and let down by the lack of good documentation. But I would be wary of moving away from GITC unless you know what clauses are important for your given requirement. It would be good to have a consistent engagement model for all contractors though.

Clause Bank

There is an additional document at the bottom of the template table called the Clause Bank. Actually, it used to be a direct link to the document, now it takes you to a new page with the Clause Bank document along with duplicated links to the guidance notes. Something has gone a little a awry there and I assume it is an unfinished thought linked with the desire to hide this document and the guidance documents from non-Government viewers.

The Clause Bank is the equivalent to the previous Additional Provisions document under the old framework. It is in its infancy with only a limited number of clauses and a lot of place holders for future clauses to be provided. As always, this is useful and there are some gems in there including clauses to reinstate the role of Project Manager, which has disappeared from the new framework.

Guidance Documents

When will we see the new frameworks used

Conclusion

Generally speaking, in my humble opinion, the new frameworks are a step in the right direction. This is only the first release of a radically changed approach to Government Contracting for Queensland, so you are going to expect a few teething problems. As with any contracting framework, especially new ones, don’t take shortcuts by accept the terms as they are and always be very wary of using the simplest contract levels. If you carefully consider your requirements and ensure you either understand the market well or allow suppliers to provide input to the final contract with more complex requirements, then this model will be a lot more flexible and far easier to manage and enforce that the previous framework.

As with any new solution, there have been and will be many changes to these documents as the holes are found and closed, so make sure you regularly check for the latest versions. I have noticed IP clause changes in the course of writing this blog and I have little doubt there will be more adjustments as more departmental legal eagles have their say. Another exciting step in the evolution of the contracting frameworks for Qld State Government is the release of an ITO for a service provider to undertake a review of the GITC framework. While this is a pretty good model, it is very complex for casual users and does not scale down for smaller procurements very well.

Over the years I have heard it said many times that “…once you get the contract signed, you chuck it in the drawer and get to working with the supplier to find a way to deliver the requirements”. In fact someone said it to me quite recently. Many people see the procurement process and resultant contract as a necessary evil so they can get a purchase order raised to pay the supplier, and little more. Often this is perpetuated by overly complex procurement processes, documents and contracts. I have little doubt many legal units will argue that the new frameworks are too simple, but a simple contract that is being used is more powerful than a complex contract that is in the drawer. Providing simplified, easier to understand contracts allows procurement teams and suppliers to focus on properly documenting requirements to allow the contract to be a useful tool. Sure you have to manage risks, but maybe it would be better to do so by ensuring there are easy to understand guides and recommendations for managing those risks rather than a complex catch all contract.

I am looking forward to shifting to this model. The documents are simpler, easier to use and understand than the old model and it gets rid of the pointless short-form v004 contract. Take a look and let me know what you think.